Migraines in Children

Migraines in Children - Steven Leber , MD Ph.D. Pediatric Neurology - 2018 Partners in pediatric Care CME - C.S. Mott Children's Hospital Migraines in children: Guidelines for primary care management of headache

Differential Diagnosis of Different Types of Headache in children

So when we're talking about headaches in kids, there's no disclosures here, it's very easy for us to makes lists like this of what's a primary headache and what's a secondary headache. Where a primary headache is if you treat the problem, you've got it solved, whereas a secondary headache is a headache that's due to an underlying cause and you really have to find the cause.

Primary Headache :

Most of the headaches we see in kids are migraine headaches. We'll come to tension-type headaches. It's very, very unusual to see cluster headaches in kids.

Secondary Headache :

Secondary headaches are fairly common.

Most of the time they're fairly easy to recognize.

- And probably the most common we see is because of depression.

- When people have sinus disease it's usually fairly straightforward.

- Tumors and mass lesions we'll talk about in terms of increased intracranial pressure, similar to with hydrocephalus. I'm not gonna have enough time to talk about pseudotumor. But these all present with increased intracranial pressure.

- Meningitis is again usually fairly straightforward with a stiff neck and meningeal signs. Although these might not be present in kids under two years of age.

- Subarachnoid hemorrhages happen in kids, they're much less common than adults. But if you do see a sudden onset of a worst headache of somebody's life, then you have to think about it. Usually you can diagnose it with CT scan, but about 8% are missed and you need an LP for that.

- Seizures commonly have headaches postictally. So it's not unusual for a child who has a seizure to have the seizure resolved and have a headache. It's fairly unusual for a headache to be the sole manifestation of a seizure. And it tricks us sometimes because the headaches tend to be brief, come and go periodically throughout the day. But most of those headaches that come for a few seconds or a couple minutes and go away, are really benign headaches. And we see them pretty commonly in kids. In young kids we see those waking the kids up at night.

- Temporomandibular joint dysfunction can present with headaches but perhaps more commonly, headaches can result from teeth clenching. If you keep your fist contracted for an hour, you build up lactic acid, you get headaches. The same thing with people clench their teeth at night. It's sort of a reflex when somebody, a kid presents with a headache to send 'em to an eye doctor to get their refraction checked. That's pretty unusual as a cause of a headache. If you do cross your eyes, your pupils constrict, your depth of focus increases, like you're stopping down an aperture of a camera and you can see better and that can give you a headache.

- But most kids don't do that. On the other hand, sleep problems are real common causes of headaches. Kids not getting enough sleep, sleeping poorly.

- High blood pressure can cause headaches, but it also can result from increased pressure. And then, more and more kids are drinking lots of caffeine energy drinks and withdrawal can cause seizures, headaches.

- Classically you have progressive headaches that worsen with lying down.

- Because there's high pressure, they wake you at night and are present first thing in the morning.

- They can be associated with mental status changes.

- Nausea and vomiting, but though these are really not specific 'cause we can see those with migraines.

- And obviously papilledema.

- You can get a sixth nerve palsy, reminding you the sixth nerve controls the lateral rectus so your eye tends to go inward because you can't abduct the eye. This is a false localizing thing as sixth nerve gets compressed or stretched.

- In infants who have high pressure, they can develop macrocephaly or bulging fontanelle,

- Or can have something called sunsetting in which the pressure in the midbrain keeps their eyes from going up, so it looks like their eyes are setting in their orbits.

Tension-type headaches:

Described as aching, kind

of non-specific complaints.

Often resolved with minor

over-the-counter analgesics.

Typically no nausea or vomiting

but increase with stress.

But the increase with stress

is certainly not specific.

That happens with migraines.

Migraine with aura.

So about 10 or 15% of

migraineurs have an aura.

They don't have to have

it with every headache.

- An aura is a neurologic dysfunction. So it can be a negative thing, I lose my vision or get blurry vision, or a positive phenomenon, I see things that aren't there, sparkles, dots, zig-zag lines. If they have a unilateral headache, the aura is usually contralateral to that. And visual symptoms resulting from occipital involvement are most common, but you can have sensory, motor, language, cognitive, or cerebellar dysfunction.

- The visual symptoms. Classically you have, this is where you're looking, a zig-zag line that's expanding and leaves a scotoma behind.

- But you can get sensory, motor, or language like I mentioned.

- The headache is usually throbbing. In adults it's classically unilateral. In kids it's more commonly bilateral. It can be frontal or temporal, although sometimes we see them occipitally. Gradual onset, going on over minutes to hours. Classically two to six hours. Usually it's shorter in children than adults. And classic for migraines, activity worsens the headache. So running in gym class, going up stairs. And it's very classic for sleep to improve the headaches. Even sometimes a nap.

- A lot of GI symptoms, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting.

- They can get very tender to non-specific things. So somebody has a migraine, you touch their forehead, it hurts. That's a phenomenon called allodynia.

- And then very classically, photophobia or phonophobia. Light or noise sensitivity, one or both, but not always.

Migraine without aura

- Migraine without aura is more variable.

- There's often personality changes, a vague dizziness, malaise.

- The headache may be unilateral and pounding, often hard to describe. Again can go on for variable periods of time. And classically when somebody has a migraine with aura, they throw up, they feel better. With migraine without aura, that tends not to happen.

Triggers of Migraine :

- Triggers, most of the time people have migraines, there's no specific trigger. But the ones we see are stress, head trauma.

- But even without a concussion, just lightly bumping your head can bring on a migraine, heading a soccer ball. Certain foods, that's fairly uncommon.

- When they're doing careful studies, maybe 10 or 15% have a specific food trigger.

- Menstrual cycle, so 60% of women have worsening of their migraines with their periods. And 15% have exclusively with their periods. Even if you get enough sleep, changing your sleep habits will often bring on migraines. So staying up late Friday night and Saturday night, bringing on headaches later.

- Missing meals is classic.

- And then certain odors such as perfumes, very classic for bringing on headaches.

Family history.

So if you had to guess,

what percent of children

with migraines have a family

history of one or both parents?

Just think about it for a second.

It turns out to be 80 or 90%.

Now the issue is getting the history.

So I can't tell you how

many times I've asked,

Does anybody get migraines?

The answer is no.

Well I'm gonna start Billy on medicine X.

Well that didn't work for my migraines.

I thought you didn't get them?Well, I don't, I used to.

Or, I don't get migraines,

I get sinus headaches.

I get sick to my stomach, I see sparkles

and lights and noise bother me

but it's because of my sinuses.

So you really have to ask,

does anybody now get headaches

or get headaches in the past?

Migraine variants :

- The other things that's specific to pediatrics or more common in pediatrics is migraine variants. A lot of what we see aren't really presenting with the headaches as much as other things. We talk about complicated migraines as migraines with a non-visual aura.

- So any of the other things that we talk about, there's ocular migraines, in which you lose vision in one eye. Most of the people that come in and say, I had a headache and I lost vision in my right eye, are really talking about a right hemianopsia. It's the same if you cover the right eye and left eye. Occasionally have a very astute kid comes in and says, I lost vision in my right eye. I could see perfectly well when I cover my right eye, and I'm totally blind when I cover my left eye. The retina's involved in the migraine. The retina we can think of as part of the brain.

- Opthalmoplegic migraine affecting the cranial nerves.

- Basilar migraines are very common, they often present with syncope. So it's two or more brain stem features. So loss of consciousness, your reticular activating system keeps you awake. Ataxia, tinnitus, double vision, the brainstem keeps your eyes aligned. Bilateral sensory symptoms as the fibers come up from your neck. We see kids with acute confusional migraines. It's basically up to 24 hours of delirium. Come to the ER, can't tell if they're have encephalitis or complex partial seizures. Then it becomes clear it's a migraine.

- You can get an aura without a headache, so the visual changes or vertigo is one of the common presentation. One of the common causes of vertigo in kids is migraines.

- Certain genetic things can cause hemiplegic migraines that run in families.

- Trauma-induced migraines. The British literature is full of people who headed a soccer ball and went blind for an hour, with our without a headache, and it's a migraine aura with that, they may not have a headache.

- There's something called benign paroxysmal vertigo. It seen in infants. So they may all of a sudden fall to the ground, look terribly distressed. The astute mother may notice the eyes are going boom, boom, boom, boom, there's nystagmus. Goes on about 10 minutes. If the kids are old enough, they may say they're dizzy. And then it goes away. They often have a family history of migraine. Often evolve into more typical migraines.

- Similarly there's something called benign paroxysmal torticollis, where, oops, skip that, where kids are like that for a day or two. They're terribly distressed, they're vomiting, and goes on and may evolve into more typical migraines.

- And then cyclic vomiting. If people who have migraines often present initially with just a lot of vomiting, evolve into migraines. About half the cyclic vomiters, are migraineurs, it's hard to know, so it's a matter of treating them. But if it doesn't work, you don't have a diagnosis, because the treatment doesn't work for everything.

Complications of migraine.

- So just real quickly, status migrainosus is having a migraine going on for 72 hours. Different from people who have chronic, daily headaches. Kids often come to the ER with dehydration, vomiting.

- Migrainous infarction, so higher risk of having strokes if you have migraines, the reasons aren't clear. Sometimes they're tiny, little things like this. But sometimes they're bigger.

- Higher risk of cardiovascular disease in people with migraines but it's not clear why.

Treatment of Migraine:

- I'm gonna focus the rest of the talk on treatment. So a lot of it is reassurance. There's a huge amount of anxiety in kids and in parents of kids who come in with migraines. A lot of times just telling them this is not a brain tumor is enough to make the headaches better, because you're relieving anxiety.

- If there's clear precipitants, we try to avoid those. Every time you smell perfume, well don't smell perfume.

- Avoiding Stress .

- Getting enough sleep, sufficient sleep.

- Abortives and preventatives.

Abortives and preventatives:

Abortive Migraine Medications :

- So just, these are better if you use at the onset.

- For most people, over-the-counter medications seem to work quite well.

- There are prescription medications, triptans that work quite well. Some are approved for kids, some aren't. Sometimes they're combined with naproxen.

- There's a number of combinations of various medications that seem to work well for migraines but sometimes not covered by insurance.

- And then the barbiturates such as butalbital seem to work but can cause kids to get really sleepy.

- A number of other medications. Occasionally we'll use narcotics but we really want to avoid those except in kids who maybe have, once or twice a year, killer headaches that nothing else seems to work, and then I'll use it for them.

- Steroids we tend to use for kids we can't break the headache. Sometimes they work, sometimes they don't. I'll use a five-day prednisone burst.

- And then we'll use a variety of antiemetics for kids who have a lot of vomiting.

Prophylactic Migraine Medications :

- Let's talk about a few preventative medicines. For a primary care doctor, what I would recommend is getting familiar with one or two preventative medications, getting comfortable using them and feel free to use them. We use preventative medicines in kids who have at least one or two headaches per week, particularly if they're moderately severe.

- We'll often use them for six to 12 months if the kids are doing well, then we'll taper the medications.

- I'll go through some of the medications we use, but we tend to use antihistamines, tricyclics, calcium channel blockers, seizure preventatives, and beta blockers.

- Cyproheptadine is the one that's the easiest to use. It's an antihistamine. It comes in a liquid, it comes in a four milligram tablet. Typical dose for a really little kid, start with two milligrams a day. It's usually divided BID, but because it makes people sleepy we sometimes just give it at bedtime. And it seems to work quite will there. The two main side effects are sleepiness and weight gain. Small kids seem to tolerate it better than teenagers. But if I have a very, very thin teenager who can't sleep, I'll often use it in that situation as well. It works quite quickly, so I'll sometimes use it when I really need to treat headaches urgently.

- Tricyclics either nortriptyline or amitriptyline. My sense is amitriptyline works better but has more side effects. Comes in a variety of pill sizes. Usually start, what I tend to do is I start low, because I don't want people to have side effects. Usually 10 milligrams at bedtime and build up weekly. I used to build up toward 75 milligrams at bedtime, and now I go toward 30. May have a month or two latency of onset. Lots of side effects, sleepiness, orthostatic hypotension, you can get dry mouth, weight gain, mood changes. The most dangerous side effect is arrhythmia so I really wanna make sure there's nobody, they're not suicidal, there's no little kids at home. And I'll, I tend to use them as a 1st line drug, but also in kids with chronic, daily headaches. I tend to get an EKG first. Ron can say whether it's cost effective or not. But what tends to happen is I build up to a large dose eventually and I see these little changes in the EKG. I'll go to the cardiologist, I'll say, "Is it from the tricyclic?" They go "I don't know, what'd it look like "before you started?" So I tend to get them but.

- Topiramate is an anti-seizure medicine. It comes in tablets, sprinkles, you can make a suspension. We use much smaller doses of this for migraines than we use for seizures. So I'll tell a teenager I'm using what I use for a six month old with epilepsy. Large number of side effects. Most common are loss of appetite, and not sweating. But it can cause a lot of confusion, word-finding difficulty. You know, why did you put me on Stupimax? But I tend to use it as a 2nd line medication or in overweight patients because of the weight loss.

- We tend to use verapamil in kids. It doesn't work on adults. It can take a long time to work. I usually start it at 80 or 120 milligrams a day. The 120 has a long-acting form. Again, may take a month or two to work. The two most common side effects are orthostatic hypotension and constipation. And I tend to use it for complicated migraines, patients with non-visual auras although there's very little if any data to support that. And then there's a number of people who are using combinations of vitamins and cofactors.

- A number of commercially available combinations. People tend to use these when there's a preventative needed but really, parents, I don't want my kid on a medicine, but I can use a combination of vitamins. Not a lot of data about whether they work or not. What works best? So there's finally a multi-center trial called the CHAMP study published in the New England Journal in November 2016 comparing amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for migraine. Primary outcome was 50% reduction in headache days. Amitriptyline worked 52% of the time, topiramate 55% of the time, placebo 61% of the time. Similar for all secondary outcomes. So we don't know what to do. And they stopped it for futility. The people running this study still tend to use amitriptyline and topiramate. Maybe they weren't using enough in this study and we, you know, it's really unclear. A lot of the people in our group have gone to these vitamin and cofactors now. Because they say, well these medicines cause more side effects than placebo and they don't work as well so. But we just don't know.

Chronic Headaches :

- 20% of the migraineurs develop these chronic headaches.

- You get these patterns where these episodic headaches build up and there's a chronic headache going on.

- And they're often a combination of tension or mixed tension-like.

- They're often postconcussive,

they have dizziness

that's often vague, fatigue,

missing a lot of school.

And when these happen, you

have to look for depression,

psychosocial issues and abuse.

And we really want to avoid the situation

where they're taking, you know,

acetaminophen or ibuprofen every day.

And these are the situations,

this was the trigger . I was supposed to be using for behavioral interventions at this case, because that seems to work best in these patients.

Behavioral treatments:

So I'll talk briefly about

one of the main things

that I find most complicated

but very effective

to help with migraines and

that is addressing sleep.

So we know that kids and teens these days

are definitely overall not

getting enough recommended sleep

but there's been studies to suggest that

the migraneurs and pediatric

kids with headaches

get less sleep even than

their same-age peers.

And what we also starting to understand

is that the headaches can be correlated

with the worse sleep.

So as we're probably all expecting,

this is likely bidirectional,

headaches causing poor sleep,

poor sleep causing headaches.

The families or patients that

are presenting to your office

may have their own theory

about the direction of that,

but what we're starting

to understand is really

addressing the sleep, even

though it may be viewed

as an effect of the

headaches, can actually

really dramatically

improve their outcomes.

Optimizing Lifestyle Factors :

Sleep :

And it's important to recognize

that these other behavioral interventions

that we're gonna be

considering, are less likely

to be effective if these

kids are sleep deprived.

So some of the targets, we

often talk about screen time.

But other really helpful outcomes

or targets to consider

are the consistency.

So like we've talked about a lot of kids

have very disrupted sleep schedules

between the weekends and weekdays,

or are just like kind

of all over the place.

Like I don't normally go to

bed around the same time,

so trying to get them on a somewhat of a

consistent sleep schedule

can be really helpful.

And sometimes that needs

to be a gradual change

as opposed to a sudden change.

But I also like to make

sure I don't underestimate

the effects of conditioning

with the bedroom and the bed.

So some two recommendations

to consider with kids

are making sure that they are

only using the bed for sleep.

A lot of the kids will tell you, like,

I do my homework in bed,

and I do my Netflix in bed,

and I'm Snapchatting in bed,

and all that good stuff.

And that creates an

association with their bed

and their bedroom that this

is not a place for sleep.

So it's a pretty powerful

effect to remove all of that

from the bed, only do

sleeping activities in bed,

and see if that starts to have an effect

after done consistently

for a little while.

Similarly, a conditioning effect can occur

when they're tossing and turning,

having difficulty falling asleep at night

or waking up frequently.

So we try to break that cycle

by getting the kids out of bed

when they can't fall asleep.

Engaging in a quiet,

non-screen related activity

and going back to bed when

they are ready to go to sleep.

So picking and choosing, experimenting

and trying to find what

recommendations work for them.

And I do this process usually through

just some simple

motivational interviewing.

Help engaging them in problem solving,

as opposed to telling them what to do

'cause they've been told all

over again to sleep better.

So sometimes that gets you

a little better success.

Stress reduction :

Relaxation and Biofeedback

Stress reduction is another

big area that we consider

with managing headaches and

migraines through behavior.

We really view this as a

self-management approach.

This is something that

the child or teen can do

for themselves to help their symptoms.

And when practiced

regularly, can actually,

there's a meta-analysis a little

while ago that showed that

about 50% of outcomes were improved

in about 50% of pediatric patients.

So that was sometimes frequency

or duration or intensity.

Which a lot of these kids would view

as a very significant improvement.

So some common relaxation

strategies that are taught

and that I do with my patients

are diaphragmatic breathing,

progressive muscle relaxation,

and some guided imagery,

personalized to what works for them.

You should know of course

there are many apps,

podcasts, things like YouTube clips

and yoga can all be helpful as well.

Many of you have heard about biofeedback

and it's really exciting

but I really try to remember

that it is an adjunct to relaxation.

It's not a tool that's

gonna heal the child

in and of itself.

But what it does is it really provides

either auditory or visual kind of feedback

about what they're doing to

their body when they relax.

And it can be very empowering.

It can help them understand

what they're doing

and motivate them to stick with it.

So there's a number a variety

of modalities that we use

from pretty low tech to high tech.

But all it does is it really shows the kid

this is what you're doing to your body

and we teach them a little bit about

this is a mechanism,

this is what's happening.

And if you practice regularly,

this is something that can

be really be helpful for you.

But again, it's that regular practice.

When to refer to a Psychologist ???

- So in our well-rounded, comprehensive treatment of headaches, you may at some point consider referring to a psychologist to help with persistent chronic or episodic headaches or migraines.

- Some of the things you might want to bring a psychologist on board to help with are things like, when they're not adhering to medication regimens.

- When they're avoiding a lot of school they say because of the headaches and migraines.

- If you already know or have identified presence of depression, anxiety, or other health conditions that may impact their headaches or how they treat their headaches. Or if the family just expressed an interest in non-pharmacological pain management, this is a great place to have a psychologist come out and help.

- So things like, I'm worried about my headaches, or my headaches are making me not perform as well in school. And when there's kinda mild depression or anxiety symptoms present. I can usually detect that by saying like, what are you stressed out about? As opposed to like, do you have anxiety disorder?

- But if depression or anxiety is much more generalized, pervasive, disruptive to life, that's when I would really consider primarily addressing those, and hopefully that will help address the headaches, and maybe pain psychology can be an adjunct to that but primarily kinda considering the depression or anxiety.

Headache Evaluation :

- So when you're evaluating a headache what you wanna look at is blood pressure, the head circumference particularly a small kid.

- Whether they have sinus tenderness. You wanna do a good, careful neurologic examination, including looking in their eyes.

- Look for depression, look at sleep.

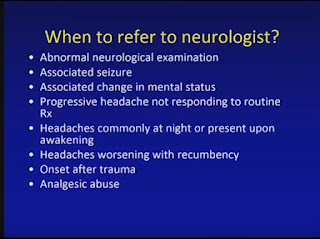

- And I don't know the right answers for all these. So we wanna do an imaging study, preferably an MRI, when there's an abnormal neurologic examination, when there's signs of increased intracranial pressure, that is the headaches are improving with sitting up or frequently wake the kids at night. Although I have to tell you, most of the headaches that wake people at night are migraines.

- When there's a progressively severe course, or even a change in the severity or the quality of the headache, so kids with migraines can develop brain tumors and we can't forget that.

- Abnormal neurologic examination, there's associated seizures, changes in mental status, things you're doing just aren't working.

- Other signs of increased ICP, onset after trauma or they're abusing analgesics.

- The role of the primary caretaker, I think you have to be able to diagnose migraines and know when the headache is more worrisome than being a migraine.

- Know when to image and when to refer or do one or the other.

- Be familiar with abortive medications and I would say at least two preventatives, and feel free to use them, that's really your job. Let's lead into a program we're just starting. We're totally overwhelmed with referrals for headaches. And it's making me sick but our wait time now is about 14 months to get into our clinic and we're not taking people who have not been on preventative, not failed a preventative. But we wanna do better for the kids and for you guys so what we're starting is something called Pediatric Headache ECHO.

- So this is a program that we're just starting. It's to train primary caretakers in terms of how to take care of kids. So this is a telementoring program where we're gonna have a series of eight sessions. Each one if gonna be about 15 or 20 minutes of didactic talks, but then the rest of it's going to be case presentations that the participants, and there'll be about 20 participants, you know, per round of eight sessions, we'll present their cases and discuss 'em with the experts and with each other, the idea being that you really become experts at treating the headaches and can manage them on your own. It'll allow us to see the kids we really need to see in the clinic faster, and allow your patients to get managed faster and better without having to wait. So you'll be getting publicity on this, it's getting started at the end of May. And we're actually really excited about starting. There's a family that donated money to support a coordinator for it and it'll be a fun thing, thank you.

Dr. Steven Leber, pediatric neurologist at C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, presents best practices for primary care management of migraine and headache in children.

Presented at the 2018 Partners in Pediatric Care CME.

No comments:

Post a Comment